Pattern is an underlying structure that organizes surfaces or structures in a consistent, regular manner. Pattern can be described as a repeating unit of shape or form, but it can also be thought of as the “skeleton” that organizes the parts of a composition. It is one of the most effective ways to unify a painting.

A compositional technique that is not new, Pattern can be found in ancient Chinese, Egyptian and Greek art. It was used extensively as a mode of design by artists in the 17th century when the chiaroscuro technique became popular. Chiaroscuro is a method of painting using strong contrasts between light and dark.

An excellent example of pattern is “Descent from the Cross,” by Peter Paul Reubens. In this painting, the eye is drawn first to the white drapery, and then to the figure of Christ. The eye flows downward from the upper right side toward the lower left and then the middle, with strong contrasting shapes, using light values and vibrant color.

Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee

by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

Another example of pattern is Rembrandt’s "Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee," where the lighter values emphasize the focus of the painting, while the darker values deemphasize everything else around it. The brightest shapes, the waves that are lashing the boat and the crew that is struggling to manage the sails are bathed in light, while the rest of the passengers, including the sleeping Christ are in shadow.

Creating Pattern

Pattern can be a large shape (or a grouping of shapes) within a picture that forms an abstract design. You can create this shape by connecting dark or light shapes of a subject against a contrasting background. Sometimes nature provides a ready-made pattern. Other times, as in still life setups, you can manipulate your subject to achieve an interesting pattern.Patterns in Nature

Peter S. Stevens, a Harvard biologist, in his book entitled “Patterns in Nature” claims that there are only a finite number of ways that patterns can be structured in nature.

He says that pattern can be classified in five different ways:

- Flow

- Branching

- Spiral

- Packing

- Cracking

Branching occurs in the plant world in trees and many plants, but it can also be seen in geological formations, including river deltas.

Galaxies form Spiral patterns, but you can also see evidence of spiral patterns in the opening “fiddlehead” buds of ferns and in nautilus shells.

Packing refers to the way in which compacted cells define each other’s shape. A densely packed cluster of mushrooms will grow together, deforming the circular form of each cap because of crowding.

Cracking Surfaces (like mud or old paint) that shrink as they dry may experience cracking, resulting in a similar cellular pattern.

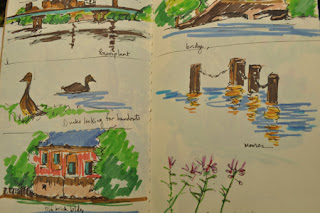

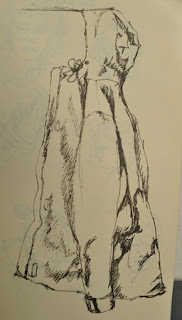

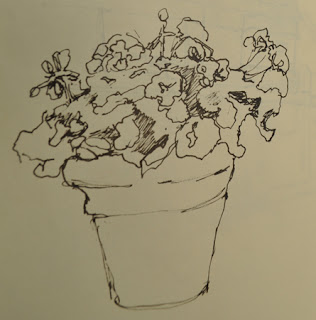

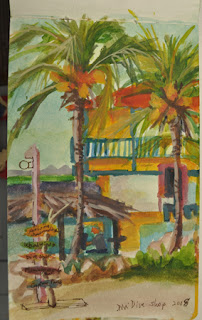

It doesn’t matter how good a sketcher you are. The beauty of urban sketching artwork is the informality of it. You can sketch anything, anywhere, and you don’t need to produce a finished design. You will find that your drawing accuracy will improve with practice, and so will the way that you look at things.

It doesn’t matter how good a sketcher you are. The beauty of urban sketching artwork is the informality of it. You can sketch anything, anywhere, and you don’t need to produce a finished design. You will find that your drawing accuracy will improve with practice, and so will the way that you look at things.